[Consumer Reports] The Hidden Costs of Credit Karma, Credit Sesame, and Other Credit Score Apps

Originally posted on Consumer Reports

By Lisa L. Gill

Most don't produce reliable scores, and all have unnecessary charges and pose privacy risks, Consumer Reports finds

Photo Illustration: Lacey Browne/Consumer Reports, Getty Images

Janet Ha Andrews, 33, of Redmond, Wash., started using Credit Karma several years ago as a new U.S. citizen to help build and monitor her credit. But when she went to purchase a car earlier this summer, she says she was dismayed when the dealership said her credit score was significantly lower than the one the app showed her.

New York City resident Alfred Bonnabel, 66, says that because he’s had poor credit in the past and is trying to get into a better financial position, he planned to sign up for the free Experian Credit Report app. But somehow he accidentally “tapped the wrong button” and enrolled in a higher tier of service he had to pay for.

Like most consumers, Ha and Bonnabel understand that their credit score matters—a lot. Having a good one means you can get a loan or open a credit card account with a favorable interest rate. And because the scores can also be used by others—from phone and utility companies to car insurers and even prospective landlords—to make decisions about you, these scores have money-in-the-bank value if you can get them high and keep them up.

But to get access to these scores, you usually have to pay, or hunt for them as a perk from a bank or credit card company. So it’s perhaps no wonder that an entire industry has sprung up to give people access to their credit scores and help them keep track of their movement. Credit Karma alone says it has 100 million users.

But despite their popularity and promise, an investigation by Consumer Reports of five apps that provide credit score monitoring—in addition to Credit Karma and Experian Credit Report, they are Credit Sesame, TransUnion Score & Report, and myFICO—in fact have significant drawbacks and few upsides. (Download a PDF of CR’s credit app methodology.)

Chief among these: All collect and share more data about you than they need to perform their core functions, according to CR’s experts, mainly so that they can upsell you other products and services. And most do not provide access to the type of credit scores that can meaningfully help you.

Stress Testing Credit Apps

To examine the apps, CR’s experts downloaded and signed up for each of the five. For the two that charge for their services, they paid the enrollment fees of $19.95 for myFICO and $24.95 for TransUnion Score & Report.

CR’s experts then pored through the apps as well as their websites, reviewing their privacy policies and terms of service agreements.

One goal was to understand what type of information the services collect from and about users, and how that information is shared. To that end, CR’s code experts also performed a type of digital “track and trace,” to find out whether the apps were communicating with third parties.

They learned that for the benefit of seeing a credit score, consumers must, perhaps unwittingly, agree to give up substantial amounts and types of personal and other data that “may then be shared beyond the parties listed in the app’s privacy policy,” says Bill Fitzgerald, the researcher for Consumer Reports Digital Lab who led the privacy policy review.

Further, by signing up, consumers make themselves subject to a steady stream of offers and advertisements for financial products and services. These are presented under the guise that they are personalized recommendations tailored to you, when in fact the products may not be in your financial best interest.

And, in order to use any of the apps, consumers must also agree to settle any future dispute through what’s known as mandatory arbitration, not by going to court, says Syed Ejaz, a financial policy analyst at CR who worked on the investigation.

Arbitration is a company-selected private forum for dealing with complaints, in which consumers have been less likely to prevail and generally have no right of appeal. Mandatory arbitration also almost always forbids consumers from banding together with others who have similarly been harmed, jeopardizing their ability to enforce their rights, consumer advocates say. Most consumers end up deciding it’s not worth it to even bring their claim in arbitration—so mandatory arbitration also undermines an important means of corporate accountability.

Consumers must agree to all of the above just so they can see their credit score. But there’s a problem even with that. Consumers don’t have a single credit score, but dozens, Ejaz says. Four of the apps CR examined reveal only a single score, and “that score likely won’t be the same one lenders or banks use to make a decision about whether or not you qualify for a loan or credit card,” he says.

Both Experian and myFICO give you access to other, possibly more useful scores, but they require you to pay for the privilege.

With the exception of Credit Karma, the free apps also charge consumers a fee to access their credit report. That’s the file maintained by the three major credit agencies—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—cataloging your credit card, mortgage, and other loan and financial history, and that your score is based on. But you can check your credit reports free through AnnualCreditReport.com, a website run by those credit agencies, as mandated by federal law. Until April 2022, you can do that weekly; after that, you can do it once a year.

Overall, using a credit app is a tradeoff that could do more harm than good, says Ed Mierzwinski, senior director for the federal consumer program at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, a consumer advocacy group, who was not involved in the evaluations of the apps and is also a CR Board member. “You give up a tremendous amount of information, and allow these companies to collect a vast amount of information so that they can give you for ‘free,’ or worse, sell you a credit score that is not used in the real world,” he says.

But that these companies see financial opportunity in making credit scores available to consumers is problematic by itself, Ejaz says. “The only reason credit apps exist is that consumers don’t have a right to access the kind of credit scores that really matter,” he says. “That’s why CR supports the Protecting Your Credit Score Act of 2021, which would establish a secure portal where consumers can access their credit reports and scores for free and an unlimited number of times.”

The bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Josh Gottheimer, D-N.J.

CR asked all five companies about their consumer privacy, data collection, and data sharing practices. They emphasized that they take consumer privacy very seriously and that consumer trust is paramount to their business.

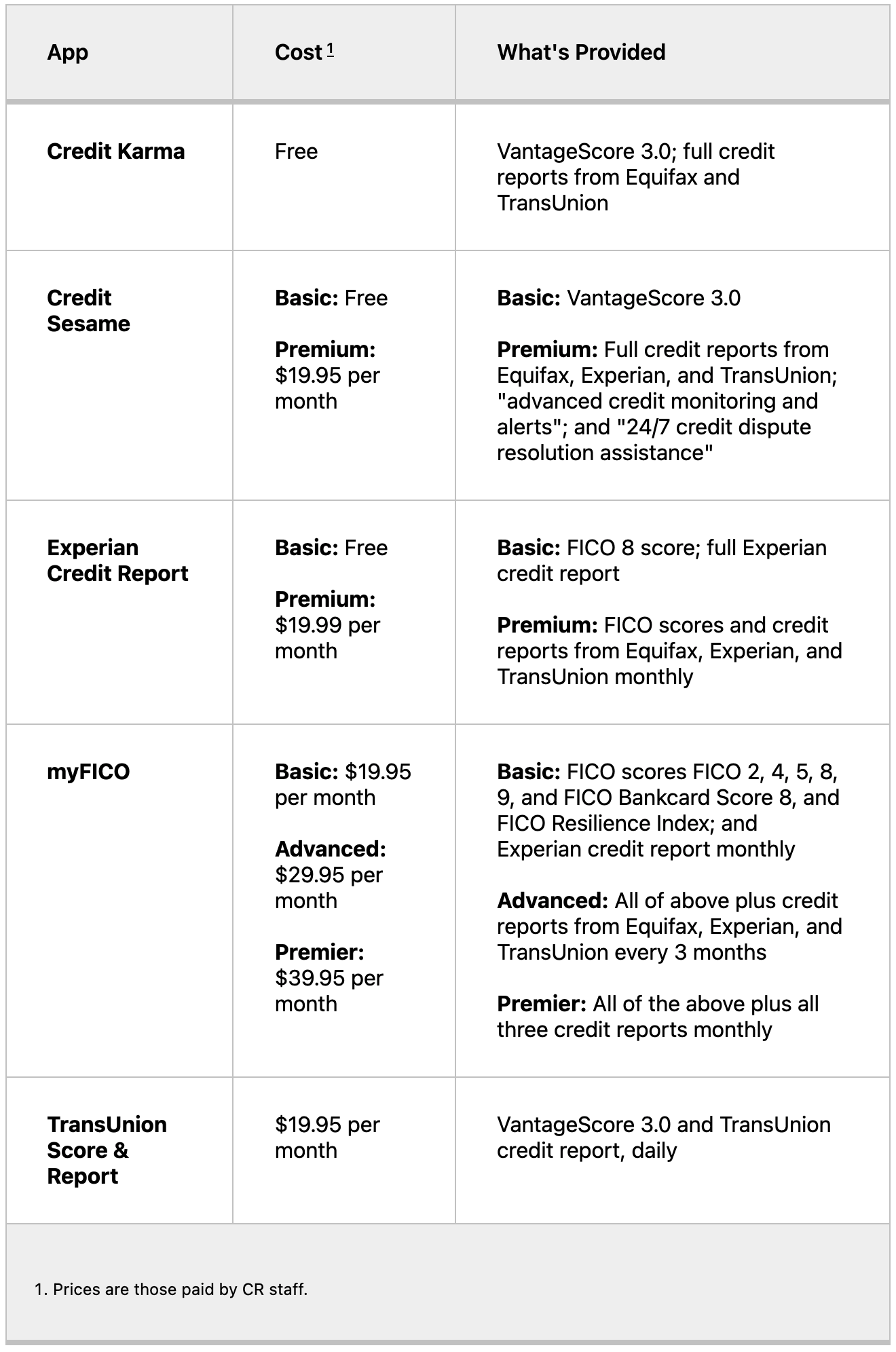

Credit Apps: What They Cost, What You Get

Two of the credit apps CR looked at charge monthly fees for their basic-tier services. And even those that don’t come with downsides. For example, the VantageScore 3.0 offered by several has limited value because many lenders don’t use it, and the credit reports many of the apps offer, often for a price, are available free through AnnualCreditReport.com. Moreover, all of the apps gather and share a lot of data on you, and may heavily market to you with offers of credit cards or other products you don’t need or want.

Signing Away Your Data

Before you can create an account on any of these apps, you have to agree to a terms of service agreement, which is lengthy and confusing. They’re written in “legalese that many consumers won’t be able to understand,” Fitzgerald says.

And by accepting those agreements, you grant the companies a lot of power. Buried in those agreements are broad statements giving the companies permission to collect your personal data not just from your use of the app but also from other sources.

The goal is to build a kind of “digital dossier” about you. Such digital profiles, Fitzgerald says, are not just filled with details about your credit history but also may include information about where you live, work, socialize, and shop.

For example, Credit Karma’s policy allows it to gather information about you from “local business reviews or social media posts,” which implies it could engage in some form of data scraping or collection of business reviews and social media sites, Fitzgerald says.

The policy also states that it can receive your “employment or income data, vehicle, or driver information” from third parties.

MyFICO’s agreement says it could dip into census data or real estate records when putting together its file on you.

TransUnion’s privacy policy takes it further. It might collect your family members’ names, and your home and billing addresses, email addresses, phone and Social Security numbers, birth date, employment information, and driver’s license and passport numbers.

What’s more, the policy appears to include the right to collect data on you from “external data providers,” which CR’s experts believe is so open-ended that it could mean from virtually anywhere.

Three of the five apps—Credit Karma, Credit Sesame, and Experian Credit Report—also ask you for permission to determine your location using your phone’s GPS. Fitzgerald says that at the time of our tests, Credit Karma’s app asked for permission to do this in the background, even when the app has been minimized and is not actively being used on your phone.

Credit Sesame told CR that it uses location information to provide consumers with “instant cashback offers from retailers” and that a person must “opt-in” to this service. Credit Karma and Experian did not explain why they collect this data.

“The apps don’t need this data to run the core function of their service,” Fitzgerald says, “which is to give consumers a credit score.”

Is all this data collection legal? Technically, most of it is, but it is also under-regulated, says Raúl Carrillo, an attorney who focuses on digital privacy as an associate research scholar at Yale Law School and a former special counsel for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, because consumers sign those terms of service agreements before using the apps. But he says the agreements are so complex that it’s unrealistic to expect consumers to meaningfully understand what they are signing.

“The burden shouldn’t be on you, the individual, to figure out if these extremely powerful companies have that information at all or are using that information appropriately,” Carrillo says. “You shouldn’t sign away all your privacy rights just by clicking on ‘I agree.’"

The Apps Spread Your Data Around

Where does all that data go?

TransUnion says it sells your data to third-party companies. Only California residents can opt out, by selecting a “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” option. The privacy policies for the other four companies state that while they don’t sell the information, they can use it to market products or services to users.

To track exactly where the data goes, CR staff members were able to observe calls made by the apps to various third-party services. Fitzgerald and his team noted that not all companies on the receiving end were listed in the apps’ privacy policy disclosures.

The common practice of sharing data this way in its own right raises privacy concerns. But credit apps escalate the problem, Fitzgerald says, due to the quantity of the information they gather, the amount of time over which they gather it, and the length of time that they retain it. This data, whether sold or simply shared, could, in theory, be used for a broad range of uses, he says.

This highlights a fundamental problem with the apps tested for this research: It is impossible for an average person to get a clear sense of where all this data is sent and how it is used.

The Apps Upsell Products You Don’t Need or Want

The point of all this data collection is that it can be used to make predictions about you—information that can be used to sell you products and services, says Carrillo at Yale.

Indeed, all of the apps CR looked at other than myFICO use this data collection to send users ads, financial offers, promotions, and marketing materials.

CR’s experts, as well as consumers who use these apps, say they were sometimes overwhelmed by offers for credit cards, personal loans, and other financial products and services.

Though the companies make it clear that they make money this way, the practice can still be confusing to consumers, in part because these solicitations are pitched not merely as advertisements but as advice.

For example, a CR staffer who subscribed to Credit Sesame for this project received an email from the app “recommending” a new credit card that “could help you increase your credit score” and “decrease your credit usage.”

While opening a new credit card account could improve your credit score because it would mean you have more available credit, that’s not true in all cases, nor would all consumers qualify for the offer regardless.

Moreover, the act of applying for credit can hurt a person’s score, because the credit card company checks the applicant’s credit report, doing what’s called a “hard pull,” which counts against you, says Chi Chi Wu, staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center. That damage occurs even if the credit card company grants you credit.

“This is the real point and the real danger of these kinds of apps,” says U.S. PIRG’s Mierzwinski. “They lure the consumer into this hive by offering a credit score, something a person can’t easily find out for free, in exchange for nearly unlimited access to their information,” he says. And that information is then ”used to ping them with countless offers and promotions, some of which could even hurt their score if they applied and were denied."

You Forfeit Your Right to Sue

Included in the terms of service of all five apps is a provision that states that you agree not to sue them over any disputes you may have, but rather to handle them through a process known as arbitration.

That’s always a concern, because the arbitration process is so onerous that few consumers choose to pursue it, and when they do, they usually lose, says CR’s Ejaz. But it’s a particular problem with the apps from Experian and TransUnion. Those two companies are not mainly app providers, but credit bureaus; that is, they actually produce the credit reports that the scores are based on.

As credit bureaus, these companies are subject to the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (PDF), which gives you the right to challenge them in court if they violate that law by improperly handling your credit information. But by agreeing to arbitration in their apps, you give up that right, consumer advocates say.

That’s concerning, says NCLC’s Wu. “Just because someone is using a credit app doesn’t mean they should have to give up the right to make a court challenge if there are inaccuracies in their credit report,” she says. “It is egregious and unfair.”

Wu isn’t alone in this view. The practice “raises many red flags,” says Edward Y. Kroub, partner at Mizrahi Kroub LLP, a consumer protection law firm based in New York City, who reviewed the companies’ arbitration policies for CR. "Consumers must understand that their right to a jury for Fair Credit Reporting Act claims against credit reporting agencies is extremely valuable. Waiving these rights is not recommended."

What You Should Do

Consider skipping the apps to protect your privacy and avoid being bombarded by ads. Some folks may not mind a company collecting data about them—sometimes a lot of data—for an easy way to keep track of a credit score. But keep in mind that the score you get may be of limited value and that you’ll be heavily marketed to.

Look for free credit scores elsewhere. Instead of signing up for an app, check to see whether your bank or credit card offers you access to your credit score, Ejaz says. Many do. Although these free scores are probably not the ones mortgage lenders use, knowing them could help you if you want to apply for a credit card or auto loan.

Get free credit reports. Don’t pay for credit reports that you can already get free. Instead, check your credit report weekly at no cost through AnnualCreditReport.com.

Correct errors in your credit report. Your credit score is only as accurate as the credit report it is based on. But, as an earlier CR investigation found, those reports often contain errors. So if you see any errors in your report, contact all three bureaus, in writing using certified mail, about it. Read more about how to fix mistakes in your credit reports.

Don’t rush to sign up for credit cards or other offers based on ads from the app. Instead, take your time to compare all types of credit cards and their terms, says Bill Hardekopf, a senior industry analyst at CardRates.com, a company that evaluates credit card offers. “There are hundreds of card offers out there. Don’t assume the one offer that lands in your email has been fully vetted or screened for you and your needs,” he says. “Doing that work is really up to you.”

Editor’s Note: This article, originally published on September 30, 2021, has been updated to include more information about arbitration and to clarify that Experian’s premium product also provides lender scores.

Consumer Reports’ evaluation of credit score apps was made possible, in part, by a grant from Flourish Ventures’ fund at the Silicon Valley Community Foundation.